Not so long ago, the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) released its final report into

long-term private rental in a changing Australian private rental sector. This report shows that the number of long-term renters - that is, people who have rented for ten years or more - is growing across Australia's private rental markets, and an increasing proportion of these long-term rental households are families with children. It makes some other interesting observations, too: long-term renters are really no worse-off when it comes to their health, but do tend to move more often, and are generally less optimistic about their financial and social well-being than their counterparts in other tenure types such as owner-occupation.

Moving house and maintaining a connection to community?

Yes, it can be done...

The report was released to minimal fanfare at the end of July, and was given a cringe-worthy run in the press by one of the usual suspects in late

September. It was said:

An alarming number of Australian families are losing sight of the home ownership dream, and being forced into long-term rental situations and struggling to provide security for their children.

Oh, dear no... not the children!

But more recently it has been picked up by other sources, and has prompted a couple of outbursts about an emerging global demographic that is being called '

Generation Rent'. (And for clarity, let's not assume that Generation Rent is actually a generation. It includes a growing number of people across a range of age groups).

One of the first mentions from a mainstream news source - that we came across, at least - was a tweet from SBS News, to which we characteristically replied with a link back to the Brown Couch:

Since then we've seen a run of articles on the issue from the Sydney Morning Herald (

here and

here) as well as the

ABC, among others. It's worth having a brief look at these articles. There are some interesting differences in the way each approaches this issue, but they all follow the same theme: home-ownership is the dream to which all Australians aspire, notwithstanding the current obstacle of ridiculously high prices. Renting is fine, under the circumstances, but we all know it's better to own your home if you can.

Even celebrity tenant/tabloid economist

Jessica Irvine, in her

'defence of Generation Rent', admits that she will one day look to buy. As she explains:

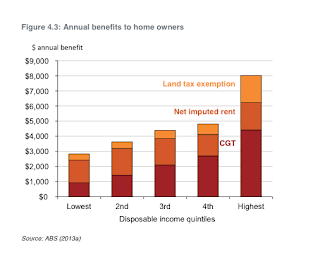

The most compelling argument for homeownership is a consequence of policy. Australians have also built our homes into excellent tax shelters. You pay no tax on any profit you make on your principal home, unlike shares or cash.

Eventually, the tax advantages of home ownership mean I will probably look to buy.

... and she's hit the nail on the head. There are compelling reasons to prefer home ownership over renting, and they are all the result of policy.

There is tax policy, as Irvine suggests, and we've spent quite a bit of time

talking about this elsewhere on the Brown Couch. These tax policies are driven by our welfare system or, more specifically, our superannuation system, which is designed to ensure our ageing population remains as self-funded as possible throughout its retirement.

Such policies are the product of both our experience and our expectations. It is, after all, deeply ingrained in the Australian psyche that we should load up on housing costs while we are young, and able to make good money. As we age into our fully-paid-off homes, we reassure ourselves, we can retire into relative financial independence. We will not become a burden on others. Our pensions will be enough to sustain us if our housing costs have already been met.

It has been this way since time immemorial - well, since about the end of the Second World War, with a quick glance back over the shoulder at the Great Depression. We have long since conditioned ourselves that the best way to save for the future is by taking on debt to buy property.

No doubt it is a strategy that has worked well for many. So well, in fact, that the idea of

not buying property has a kind of incredulous stigma attached to it - even if it is sometimes quite nuanced. The idea that you can live a meaningful, socially and financially fulfilled life as a tenant is as foreign to many Australians as the desire to buy property seems natural. As the ABS points out in its report into

Measures of Australia's Progress (2010):

Home ownership is a widely held aspiration in Australia, providing security of tenure and long term economic benefits to home owners. Owning a home can also bring social and cultural benefits such as a sense of belonging.

By implication, not owning a home can bring social and cultural detriment, and perhaps some kind of existential crisis. Because what good can come of a world where nothing belongs to nobody no more? News outlets screeching about "families struggling to provide security for their children" are more the norm than the exception, and articles like the one in the

Herald often come as a bit of a surprise. If we accept this as the normal state of affairs it is not hard to see why long-term renters would self-assess their social or financial well-being in an unfavourable way, when approached by an AHURI researcher.

... and this brings us to another reason to prefer home ownership over renting: tenants' rights. Renting is regarded as a transient form of tenure, often by tenants as much as by anyone else. Strengthening the rights of tenants is rarely at the front of anyone's mind - and if it is, it's usually only for as long it takes to say "you mean my landlord can actually get away with this?"

While it is true that consumer protection for tenants covers a lot of bases in New South Wales, there are three fundamental issues that stand in the way of renting as a secure and sensible form of long-term tenure. The first is that rights around repairs and maintenance can be difficult to enforce, so that rental housing can be in

pretty poor condition, while attempts to have it brought up to standard can be fraught. That's because the second issue is that rents can be increased almost at will,

without regard to affordability, leaving it up to tenants to demonstrate that an increase is excessive according to the market. And the third is that tenants can be asked to leave a tenancy

without any good reason.

And, when you think about it, these issues are borne of the same reasons that our tax policies so heavily favour owners. Because it stands to reason that if owning your own home is a pathway to financial independence, then owning other peoples' homes is as sure a way to wealth in your retirement as you will find. Right? So, from the outset, renting laws have set out to strike a balance between those who live in houses, and those who seek to profit from them in order to fund their retirement. That's a tricky set of interests to balance against one another at the best of times, let alone when the

players on one side are so structurally fragmented. What we're left with is a system that further entrenches the very assumptions by which it is caused: renting is not good for your long-term social or financial well-being.

This has been escalated over the last decade or so. A large cohort of our population marches towards retirement age, and our governments have looked into the coffers, over there at the pension office, to find they're running a little dry. Tax policies have been tweaked to entice more and more people into residential housing markets. They've been tweaked again to reward the faithful with all-but-assured capital gains. As first home buyers struggled to keep up, more money was poured into this system by way of grants, so that they too still had a chance to get on board. But none of that extra money was targeted to the creation of new supply, and it just pushed up prices further still. This constant upward movement quickly took the wind out of the first home owner grants' sails: in many parts of Australia these are now part of a suite of grants payable on new builds only. First home buyers are, for now, pretty few and far between.

The

withdrawal of first home buyers from the market is of course offset by the

continued rush of investors (or as they should be rightly known, speculators), all too eager to get in while interest rates are at record lows. Which means that Generation Rent - that 'new' demographic formerly known as First Home Buyers - should not expect their supply of highly-indebted landlords to run dry any time soon.

What they can expect, though, is long-term insecurity of tenure, and, if they're not careful, a view of themselves that is missing some magical secret ingredient that only the truly propertied may possess. Which brings us back to our reply to that tweet from SBS News.

What can we do to avoid 'Generation Rent' becoming a fixture of modern Australian society? Question the assumption.

Question the assumption - as perhaps Generation Rent has started to do - that home ownership is a pathway to financial independence. At today's prices, that's far from assured. You might be no better off going into retirement with a massive mortgage to service than you would be if you continued to rent - particularly if prices do start to taper off and capital gains become eroded. And as the following slides demonstrate, there has been a steady decline, over a number of years, in the rate of homeowners paying off a mortgage before retirement age.

presentation by Dr Ben Spies-Butcher.

... and, once you've gotten your head around that, question the assumption that renting should be inherently transient. Some simple changes to our renting laws - and with them, our attitude towards tenants in general - could see Generation Rent quite comfortably reunited with their sense of social and financial well-being.